The Iwo Jima War Memorial at Marine Corps Base Hawaii, Kaneohe Bay, reminds visitors of the sacrifice Marines faced during World War II.

Photo by Steve Ranson.

Every December, Americans commemorate the anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and other Hawaiian military installations that killed 2,388 service members and civilians and plunged the nation into World War II.

Hundreds of thousands of visitors travel to Pearl Harbor each year to view memorials dedicated to that devastating raid at 7:55 a.m. Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941. This year World War II veterans from Nevada attended a special memorial on the 80th anniversary of the attack.

Honoring the veterans who served during World War II, and also the attack on Pearl Harbor, though, slowly faded, beginning in the 1960s and extending to five years ago when ceremonies recognized the loss of life and the devastation that plunged the world into a global war.

The number of World War II survivors — as well as those who were at Pearl Harbor 80 years ago — continues to dwindle. Out of the 300,000 living veterans, on an average, approximately 295 veterans from that era die each day. Many of their stories have been captured in periodicals and/or books as well as narratives recorded by state and federal agencies that deal with veterans.

During the 45 months after Congress declared war Dec. 8 against Japan and three days later against Germany, thousands of men and women joined the armed forces to fight Japan in the Pacific Theater and Germany in Europe. The toll was costly. Out of 16,112,566 U.S. service members, 399,000 died.

Attack on Battleship Row

Two important monuments honor the crew of the famed battleship USS Nevada that was heavily damaged and nearly sank on that terrible day. Steve Ranson/LVN

Steve Ranson/LVN

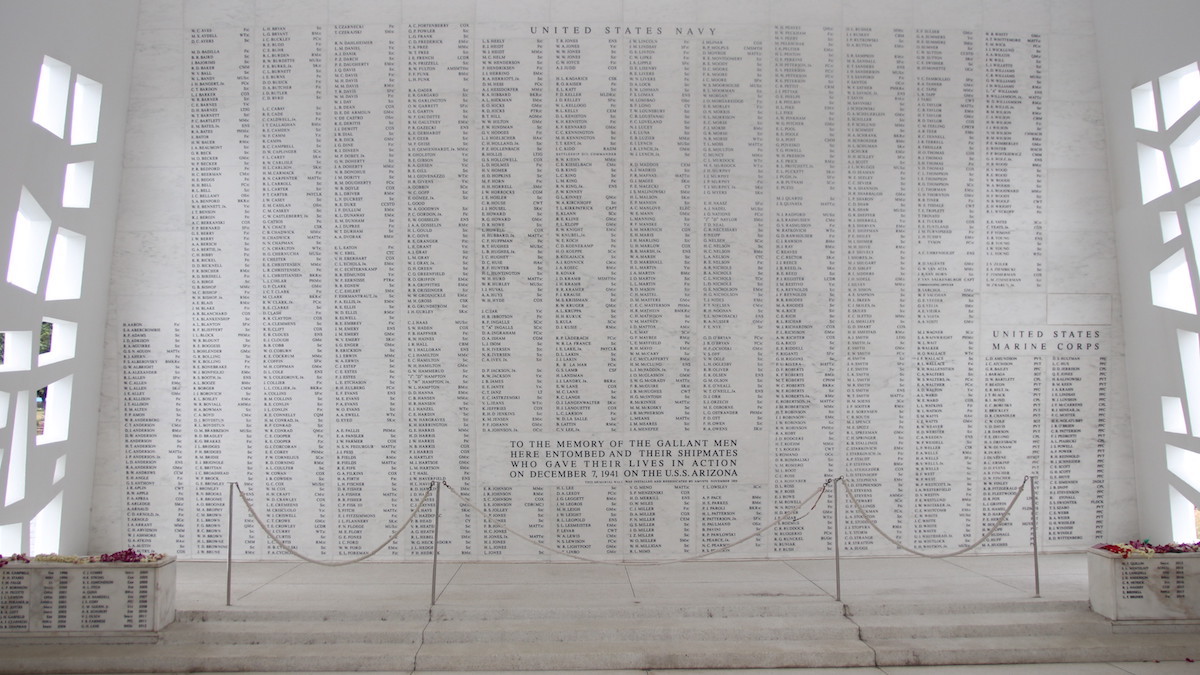

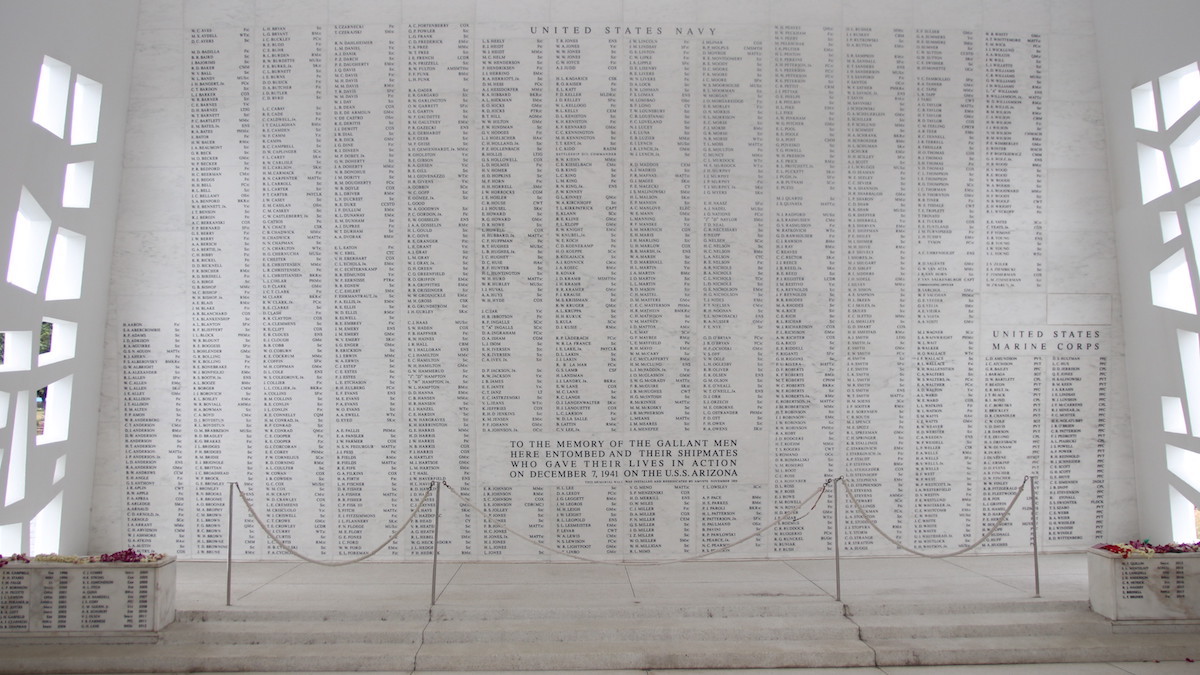

The list of more than 1,100 sailors and Marines keeps watch over the USS Arizona at Pearl Harbor.

One of these monuments, a large, whitewashed concrete slab emblazoned with the words “USS Nevada,” is located in the waters of Battleship Row near Ford Island in Pearl Harbor. The second memorial, consists of another prominent USS Nevada signboard and a bronze tablet honoring the 50 Nevada crewmen killed and 105 injured during the attack.

Following the surprise Japanese raid, the Nevada left its mooring and was attempting to reach the ocean. But the Japanese bombs proved so deadly that the ship’s officers, fearing the blazing and listing Nevada might capsize or sink in the channel, thus closing the waterway to shipping, decided to beach her on the hard sea bottom.

Two hours after the beaching, however, the Nevada floated free as the tide began to rise. By now, the Japanese planes had returned to their six carriers offshore and harbor tugs were able to move the shattered Nevada and beach her a second time.

The battleships lined up in Pearl Harbor. Named after the states of Arizona, Oklahoma, West Virginia, California, Nevada, Tennessee, Maryland and Pennsylvania, the battleships’ sterling handsome hulls protruded into the glass-faced harbor. On the other side of Ford Island was the moored USS Utah. In less than an hour on Dec. 7, an attack carried out by Japanese pilots from the Imperial Japanese Navy shattered the tranquility of a quiet Sunday morning.

Steve Ranson/LVN

Steve Ranson/LVN

Even after 80 years, oil still oozes from the USS Arizona wreckage.

Charles T. Sehe, a 17-year-old 1940 high school graduate became a sailor in November 1940. He was on the USS Nevada when she earned her first of seven battle stars during World War II. He served with his shipmates when the Nevada earned her second battle star at Attu in the Aleutian Islands May 11-30, 1943.

The greatest loss of life came aboard the USS Arizona, and to this day, 1,102 sailors and Marines remained entombed in a cold, steel casket.

Stunned, shocked, dismayed

Peggy Wertz, along with two younger brothers and two younger sisters, lived with their parents in Navy dependent housing. Her dad was an enlisted sailor.

Werts’ second-story bedroom window looked across Pearl Harbor at the USS Arizona docked at Ford Island. She witnessed a fire ball engulf the ship with the bow lifting out of the water. The shock wave followed immediately.

Suddenly, a low flying fighter with a red “meatball” painted on the fuselage and wings flew close enough for her to notice the pilot’s goggles, moustache and a grin. Another Japanese fighter clipped the top of a neighbor’s chimney.

Steve Ranson/LVN

Steve Ranson/LVN

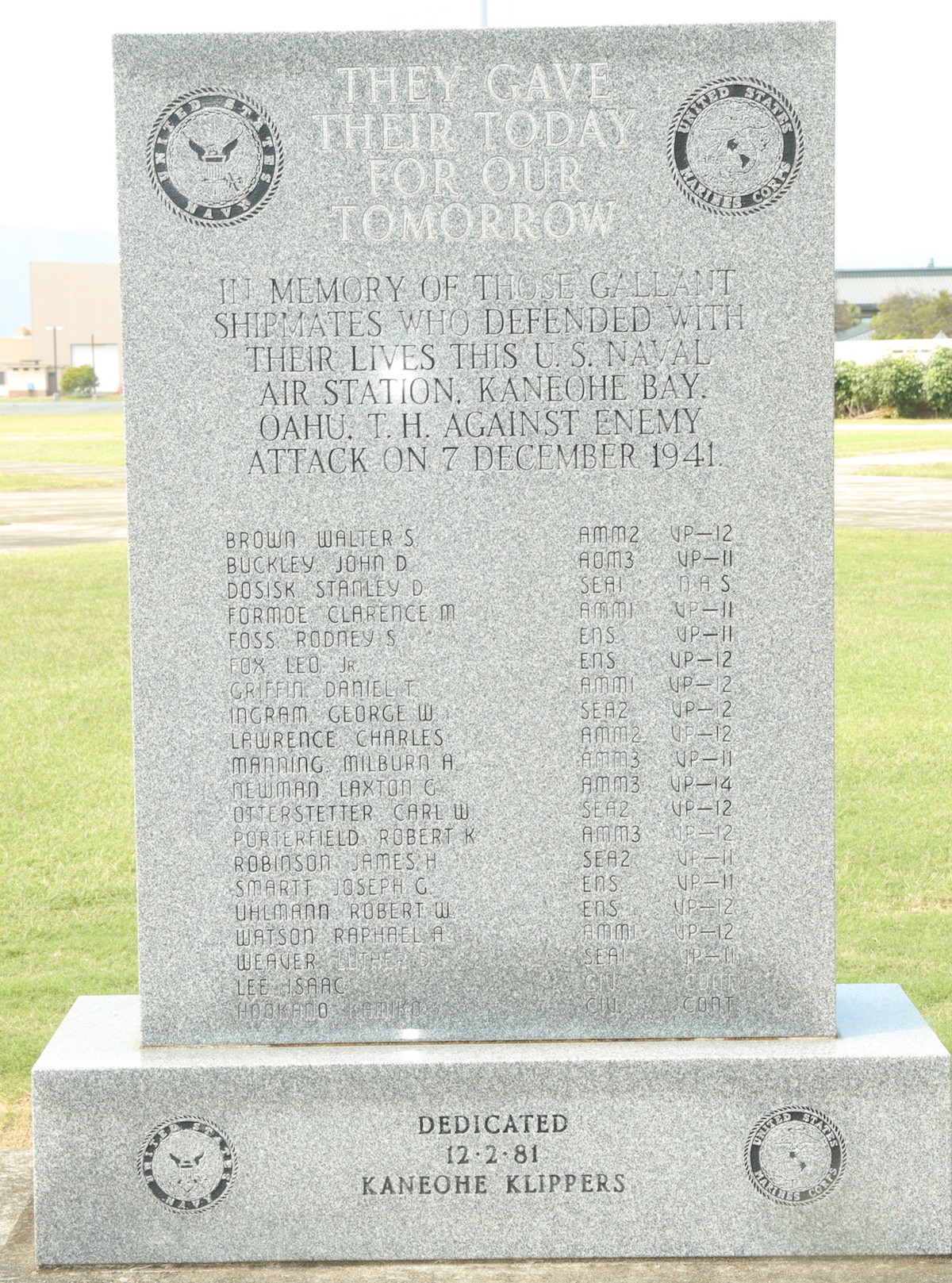

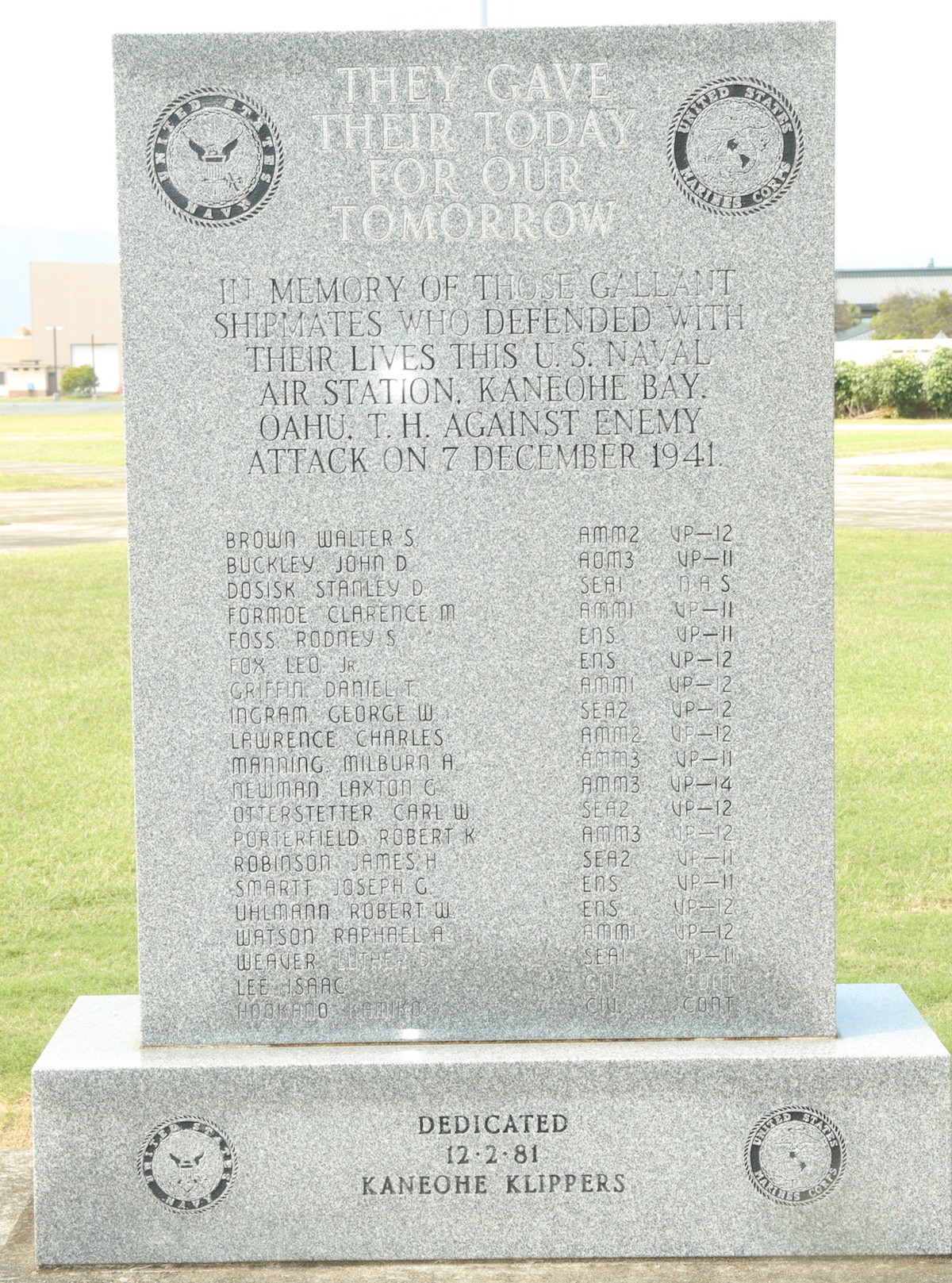

The names of those killed at Naval Air Station Kaneohe Bay, which is now at Marine Corps Base Hawaii, includes both military and civilian.

When news broke that planes from a Japanese carrier group had bombed part of the Hawaiian island of Oahu and the U.S. Navy’s fleet at Pearl Harbor, the late Nellie Nelson of Fallon, who formerly lived in Sacramento in the early 1940s with her two toddlers, leaned closer to her radio to listen to the ominous news of the attack.

“I was stunned, you bet,” said Nelson.

L. Robert “Bob” LeGoy, of Reno, who grew up in Bishop, Calif., about 185 miles south of Reno, distinctly recalled the day and how he learned more about the destruction of Navy ships.

“The only radio we could get was KMJ out of Fresno (California),” LeGoy recalled. “I made an antenna, and about 100 people gathered.”

What they heard was numbing. Torpedo bombs either sunk or heavily damaged ships, planes on the flight line were destroyed and many people — both civilian and military — died.

During his final years in high school, LeGoy remembers his friends who answered the call to join the military.

“All my friends were all trying to enlist,” he said. “My stepbrother went anyway.”

When LeGoy recently visited Pearl Harbor, on Honor Flight Nevada in 2020, he pointed to a hill that had significance. A father of one of his classmates, Judd Collins, worked on a construction crew watching the attack along Battleship Row. LeGoy said Collins had a front-row seat to history in the making.

Steve Ranson/LVN

Steve Ranson/LVN

The Japanese Mitsubishi A6M2 was the best carrier-based fighter in the world. This one is housed at the Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum.

“I heard of some of those first-hand stories,” LeGoy said when Collins, a longtime rancher, returned to Bishop.

What Collins saw were waves of Japanese planes swooping over Battleship Row, dropping torpedo bombs and strafing military targets with their machine guns. Smoke billowed into the air.

“When he saw the machine guns hit the ships, he decided to get out,” LeGoy said.

Nevadans die on the USS Arizona

Three Nevadans died aboard the Arizona — seaman first class Richard Walter Weaver, Eric Young and Richard Eugene Gill — and their bodies were never recovered.

Born in Fallon, Weaver joined the Navy on Nov. 27, 1940, and performed the duties of standing watch and serving as a gunner while on the ship. His parents were Ray Rhese and “Marge” Lois (McCuistion) Weaver. Ray Weaver, a veteran of World War I, gave him permission to enlist. Only years later, though, did Weaver’s father learn his son had been kicked out of school for arguing with his teacher.

According to information both the Reno Gazette and Nevada State Journal, the young sailor “had been sweet” on Wanda Temple, who also lived in Fallon. After he left Fallon, they traded letters. Wanda’s family moved to Honolulu in October 1941 because of her father’s employment. The Temple family invited Weaver and his Navy friends to dinner every Sunday evening.

According to newspaper accounts 54 years after Pearl Harbor, Temple called Weaver “a handsome boy-doll in a sailor suit” and ”I’ve never adored anyone as much.”

Temple married after World War II ended, and the article said she named here only child Richard. According to Weaver’s record, he earned the following awards posthumously: Purple Heart, American Defense Service Medal with Fleet Clasp, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with star and the WWII Victory Medal.

Three words summed up Young: “Big, jolly and likeable.” After Young’s death aboard the USS Arizona, the Reno Gazette described him as a popular young man who graduated from Reno High School in 1934 and then attended the University of Nevada for two years. Young was born in in San Diego, Calif., on Sept. 6, 1916.

Attending the University of Nevada kept him close to his father, James, a psychology professor. His mother, though, died in 1931. Young left Nevada after receiving an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy and graduated in 1940. Young was commissioned an ensign at graduation.

Gill attended schools in Wells and Reno and eventually earned his high school diploma from Montello High School. According to the USS Arizona Mall Memorial, Gill’s father worked for the railroad and his mother was a homemaker. When Gill enlisted in the Navy in 1940, his family lived in the small Eureka County ranching community of Beowawe where he worked as a grocery clerk.

Pearl Harbor wasn’t the only military installation bombed on Dec. 7. On the other side of Oahu, Japanese planes first appeared over the naval air station at Kaneohe Bay. Established in 1919, Kaneohe became a U.S. Navy sea plane base, the U.S. Marine Corps 3rd Regiment base and the Marine Aircraft Group 24th Combat Logistics Battalion 3 base with a 7,800-foot runway.

Kaneohe was attacked nine minutes before Pearl Harbor. Eighteen sailors died.

Medal of Honor

Bruce Van Voorhis finished his education at Churchill County High School graduating in 1924, three years ahead of his brother Wayne.

After high school, Bruce Van Voorhis received an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy and graduated in 1929. He found himself at war more than a decade after graduation from Annapolis.

On July 6, 1943, Van Voorhis and his men volunteered for a mission to destroy a crucial enemy base. Van Voorhis, who was piloting PB4Y-1 Liberator 31992 on a volunteer reconnaissance mission, and his crew died at the southernmost of the Eastern Caroline Islands near Hare Island of the Kapingamarangi Atoll.

Van Voorhis was awarded the Medal of Honor.

The Nevada aviator is also remembered at the Battle Born Memorial in Carson City and the Gold Star Family Memorial in Sparks, both dedicated to the state’s men and women who died in service of their country

The legend of Van Voorhis still etches into the history of the Lahontan Valley and with the current mission of the Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center at Naval Air Station Fallon.

This reflection on the attack on Pearl Harbor may be found in “Legacies of the Silver State: Nevada Goes to War” written by newspapermen Steve Ranson, Ken Beaton and David C. Henley. They tell of the war’s events and of the men and women who fought during World War II. To learn more or to purchase a copy, visit https://legacies-of-the-silver-state.square.site/. All proceeds go to Honor Flight Nevada.

The beginning of World War II in both Europe and the Pacific for the United States occurred 80 years ago this week. As a project to honor as many heroes and events as possible, The Nevada Appeal, Lahontan Valley News and the Nevada News Group have published numerous articles for the past two years on our local veterans who served during World War II.

Steve Ranson/LVN

Steve Ranson/LVN Steve Ranson/LVN

Steve Ranson/LVN Steve Ranson/LVN

Steve Ranson/LVN Steve Ranson/LVN

Steve Ranson/LVN