In this photo provided by the U.S. Coast Guard, a U.S. Coast Guard landing barge, tightly packed with helmeted soldiers, approaches the shore at Normandy, France, during initial Allied landing operations on June 6, 1944.

AP file

On a cloudy, windy early morning 80 years ago, the largest amphibious invasion in military history began its quest to recapture most of the European continent from Hitler’s control in what has been called “The Longest Day.”

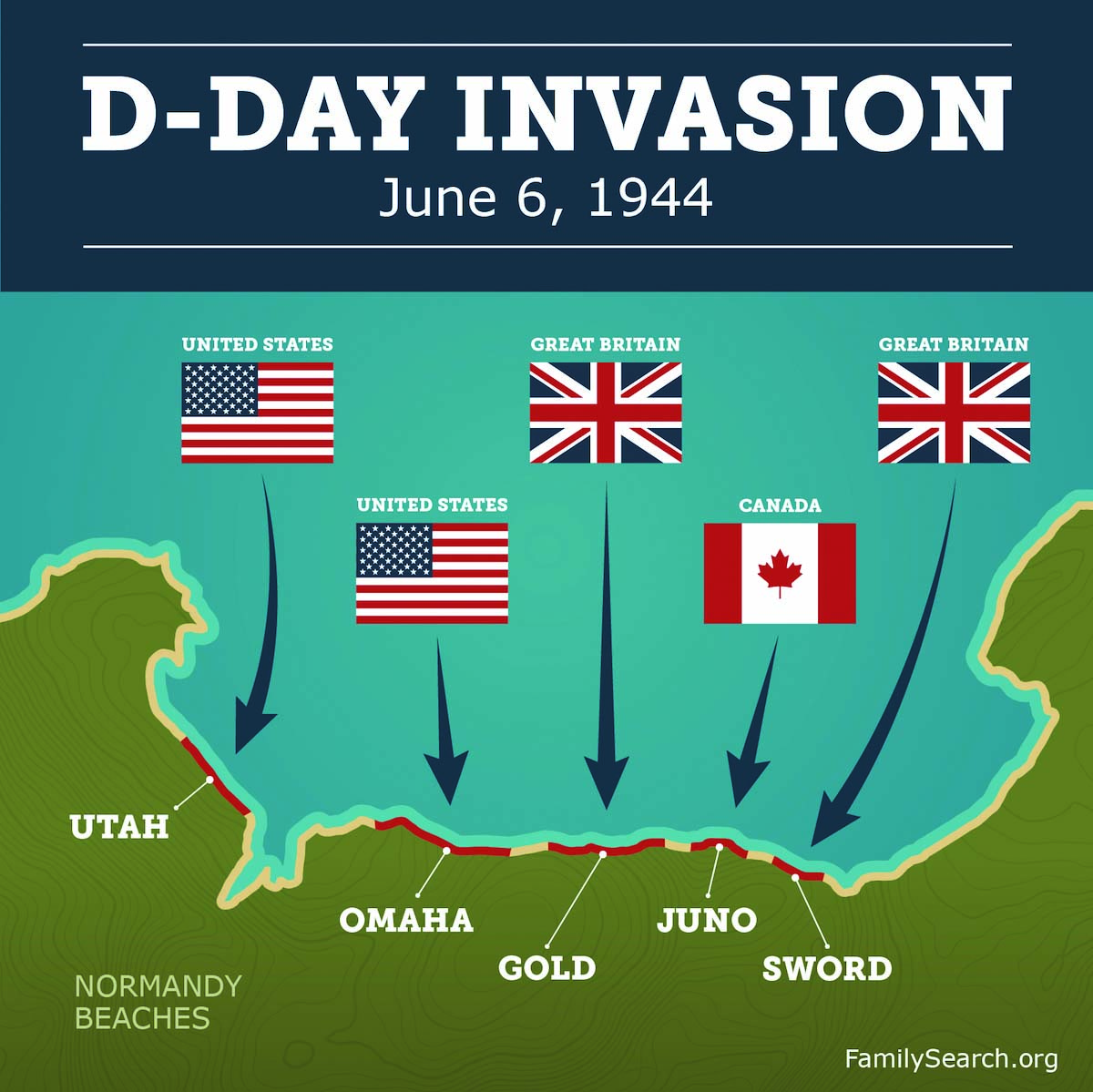

On June 6, 1944, Operation Overlord stretched along five Normandy beaches, a massive drive to push the Germans back as allied troops planned to storm across France and eventually into Germany. The invasion, informally referred to as Operation Liberation by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was immense with 56,115 U.S., British and Canadian troops, 6,939 ships and landing vessels, and 2,395 aircraft and 867 gliders. The invasion’s success became a turning point in the war.

Operation Overlord began with paratroopers dropping behind enemy lines in the predawn hours, and warplanes and Navy ships continuously bombarding the northern French coast to take out enemy artillery positions. One such ship was a Pearl Harbor survivor, the battleship USS Nevada, which fired on the Germans by trying to take out as many fortifications as it could.

Witnesses also said a long line of LCIs (Landing Craft Infantry) and LSTs (Landing Ship Tanks), an amphibious assault craft that landed on the beaches to unload tanks, extended for miles along the horizon toward the British Isles. When the front ramps on hundreds of landing ships lowered, scores of soldiers entered the water and onto the beaches with a barrage of bullets spraying at them. Scores of young soldiers, many of them barely out of high school, died instantly after German machine gun fire mowed them down during the first wave of landings.

Of the survivors from the D-Day assault, fewer than 3,000 are still living out of the 2 million Allied sailors, soldiers and pilots who participated in Operation Overlord. Approximately 119,550 U.S. servicemen and women out 16 million who fought during World War II remain alive.

BATTLE BORN, BATTLE READY

The battleship USS Nevada joined 282 allied ships that provided naval gunfire, troop and equipment transport and other support of the D-Day landings on Omaha, Utah, Gold, Juno and Sword beaches 80 years ago.

Launched at the Boston Navy Yard on July 11, 1914, the 583-foot Nevada had been partially sunk during the Dec. 7, 1941, during Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that left 50 Nevada crewmen dead or missing and 109 wounded.

The battleship, however, was refloated, towed to the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard for repairs.

During the D-Day invasion, Nevada’s 10 14-inch guns battered German land fortifications and emplacements as enemy shells fell harmlessly around her and mines floated nearby, none of them striking their target. The Nevada expended 876 rounds from her main batteries and 3,500 from her five-inch guns. Nine U.S. Navy warships and 11 large landing craft were sunk during the invasion. More than 30,000 Germans were killed or wounded and 15,000 taken prisoner.

Following D-Day, the Nevada’s guns supported allied landing operations in the Mediterranean before the battleship returned to the Pacific where it led the last WW II battles against the Japanese.

SAILORS ABOARD THE NEVADA

Richard “Dick” Ramsey began on-the-job training on board of the Nevada from the first day he was first assigned in 1943 as powder man. Training was around-the-clock and exhausting, but Ramsey, who lives in California, said the training paid off at Normandy.

More than 2,200 sailors — both officers and enlisted — made it a crowded ship, and Ramsey said there was “less elbow room” in the cramped 5-inch gun turrets when sailors would man their stations either during training or in combat.

Ramsey, who recently celebrated his 100th birthday, visited Northern Nevada in early November 2023 and placed a wreath at the USS Nevada memorial behind the Capitol.

Minnesota native Charles Sehe, another sailor on the battleship, served with his shipmates when the Nevada earned her third battle star on June 6, 1944, by destroying Nazi bunkers for the Fourth Infantry Division at Utah Beach on the Normandy coast of France.

The 101-year-old Sehe served on the USS Nevada for the entire war.

The firepower at Normandy further distinguished the battleship which was nicknamed the “Invincible Nevada.” After the D-Day invasion, the USS Nevada was reassigned to southern France and the three oldest battleships in the Navy — the Texas, Arkansas and Nevada — each had specific tasks during Operation Dragoon.

FROM SHIP TO SHORE

One man who witnessed the D-Day invasion and survived the thick of the fight was the late Kenneth Shockley of Fallon, who, as an 18-year-old mariner in the Merchant Marine, ferried troops on a small landing craft from the larger Navy LSTs (landing ship, tanks) to Omaha Beach.

Shockley, who died in 2015, maneuvered the landing craft toward the beach and then dropped the front ramp in the water to allow soldiers to run under fire.

“I lost a couple of buddies on Omaha Beach,” Shockley said in a 2014 interview, reflecting on a monumental day that left the young Ames, Iowa, native in awe of all the firepower but sad with the human carnage. “They were brothers… and one was killed outright.”

Shockley ferried soldiers to the beaches three times under enemy fire. German snipers halted scores of allied soldiers wading in the shallow water after they left the landing boats or as soon as they hit the beaches.

“They went to shore under a hail of bullets,” Shockley said. “The Germans knew we were coming, and they would just shoot everyone who tried to land.”

Shockley said everyone involved with the invasion prayed for the best.

“You get there safely or you die. That was the choice,” he added.

Yet, etched in Shockley’s mind was a horrifying experience for an 18-year-old Iowa boy who quickly grew up to be a man fighting in defense of his country, and despite good odds he avoided the hail of German bullets that came from the cliffs, easily targeting the intrepid landing ship pilot.

AN EYEWITNESS ON THE BEACH

Army Pvt. First Class Lynn Bradt, who grew up in upstate New York and later moved to Hawthorne and then Reno, witnessed the first-day attack from LCI-99, which landed on Omaha beach at H-Hour+1 or 7 a.m. The chaotic scene of soldiers wading to the shore in strong currents and high tide was harrowing to all including Bradt, a member of the U.S. Army’s 5th Division. LCI-99, though, struck an underwater mine and became immobile after Bradt went to shore in a “Duck” or DUKW, a six-wheel drive amphibious vehicle.

During Operation Overlord, 4,126 landing ships and crafts took part in the invasion, which Bradt, who died in 2020, called the most harrowing experience in his life.

Bullets whizzed by soldiers’ heads to keep the Americans pinned down on the shore until they could reorganize and begin their drive toward a long bluff dotted with German bunkers. Gunfire grew intense as one soldier described it as the rapid striking of typewriter keys on a metal surface. Of the five beaches, Omaha endured the heaviest fighting with an estimated 34,000 soldiers rushing the heavily mined beach, many of them falling in a swath of German machine-gun fire. More than 2,400 hundred soldiers and sailors died or were wounded or missing on the first day.

PARATROOPER BECOMES A POW

After spending 14 months in Europe, Army veteran and paratrooper Alfred Pawley knew he was going home, but the song “Sentimental Journey” sung by Doris Day resonated with the California native after Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945.

Pawley didn’t see much of the fighting on that June day. He, along with other paratroopers, veered off course and were captured by the Germans after they landed. Consequently, he became a prisoner of war with other Allied soldiers at a camp deep inside Germany’s heartland. As Russian troops began to descend into the area in April 1945, the German officers and guards — many of whom were older men and some teenagers — vacated their positions, thus leaving the prisoners on their own.

Many of the prisoners moved out on their own and eventually traveled more than 1,300 miles to Turkey when they boarded a boat to Cairo and then home to the United States.

Remembering when paratroopers jumped behind enemy lines, Shockley said he had heard of one place where the Germans were overrun. They retreated into a tunnel system that connected the bunkers.

Although thousands of lives from both sides were lost on June 6, Shockley said the invasion had to be executed.

“D-Day put the Germans on the run … they had to retreat,” he said.

Excerpts on the D-Day invasion are from the book, Legacies of the Silver State: Nevada Goes to War written by Nevada News Group journalists Steven R. Ranson, Kenneth Beaton and David C. Healy.