The former Evergreen Mountain View Health and Rehabilitation Center off Koontz Lane where poet Bill Cowee spent his last days in 2009. Photo taken Sept. 16, 2024.

Scott Neuffer/Nevada Appeal

Definitions of poetry can be as various as poetry itself.

“Writing that formulates a concentrated imaginative awareness of experience in language chosen and arranged to create a specific emotional response through meaning, sound, and rhythm,” reads one definition from Merriam-Webster.

But it’s even more basic than that, I was thinking driving to the Nevada Appeal office in downtown Carson City, noticing cottonwoods along the river flaring yellow, then, atop Indian Hills, traffic on Highway 395 crawling toward the capital’s outer businesses and subdivisions — disparate elements held together in a momentary tableau. Poetry, I was thinking, is a kind of attunement to the world with the verbal tools we have.

“Publishing a poem has been described as pushing a leaf over the Grand Canyon wall and waiting to hear its echo. But Bill’s volume did leave a mark — the poems rang true to this landscape and the people who make the Great Basin home,” Shaun T. Griffin, Nevada’s 2024 poet laureate, wrote of Carson City poet Bill Cowee upon the latter’s death in 2009. “He articulated a clear vision of the West — something like Gary Snyder’s vision of this place, and he did it with careful attention to detail, to sound, to imagery. No poet comes upon his or her craft with ease. Bill worked tirelessly at revision and at making each word count. What he wanted from a poem was nothing less than awe. He wanted the reader to set it down like fire at the feet.”

Cowee was celebrated in the capital city during his lifetime and in the years after his death. He is not well-known outside of Northern Nevada — at least in the mainstream press — but his poems and his friendships in the city and the literary legacy he left still inform the present, haunt the present. Failing to locate family members, I pieced together what I could from Appeal articles, tributes from fellow Nevada poets, interviews with friends and, not insignificantly, his poetry. But like any artist, parts of his life remain unknown, mysterious, lacunae in the book of his life.

What we know of Bill Cowee is he was born Nov. 15, 1942, in Wisconsin and grew up in Montana. He was “a great athlete,” according to his brother, John Cowee, in a 2009 article. In a tribute posted on the Carson City Arts Initiative website, Griffin said Cowee attended undergraduate school at UNR and completed his accounting degree at USC.

“He worked as a comptroller for the Arden-Mayfair grocery chain in Southern California before once again, relocating to Northern Nevada. For the next two decades he worked as an accountant with his brother, John, in Dayton,” Griffin wrote.

We know Cowee founded Ash Canyon Poets with John Garmon in 1987, a Carson City poetry group, and then published a collection of poems, “Bones Set Against the Drift,” through UNR’s Black Rock Press in 1997. It would be his only known full-length collection, though many other poems would surface in print.

We know Cowee spent his last years in a nursing home off Koontz Lane in south Carson. We know he tried giving up writing only to find his voice again, perhaps altered but still alive. We know the same year he died, he received his second fellowship award from the Nevada Arts Council.

“Similarly, upon urging from Terry Breeden, he submitted his poems — yes, he did start writing again — to the Nevada Arts Council. In May, 2009, he learned he was the recipient of this year’s artist fellowship in literature. This was his second fellowship award from the Nevada Arts Council. These poems were the very poems he told me he could never write. They are among the most humane of all that he has left us,” Griffin wrote.

We know on Oct. 16, 2009, Cowee died of heart failure at the age of 66. He left behind several family members, including three sons, and several friends in the Carson City poetry community who had learned from him.

One of the last poems in his full-length book, “In Pursuit of the Great ‘Yes,’” reads:

“On the pan scales of the final

balance, if the darkness of

my night makes it impossible

to lift what remains up,

I am content, no I rejoice

it is through your eyes

my final light passes.”

A portrait of Bill Cowee used to promote a 2016 tribute by the Mile High Jazz Band entitled “50th Jazz and Poetry: A Tribute to Bill Cowee (1942-2009).”

A portrait of Bill Cowee used to promote a 2016 tribute by the Mile High Jazz Band entitled “50th Jazz and Poetry: A Tribute to Bill Cowee (1942-2009).”Cowee the friend

Teresa Breeden, Carson resident and 1992 Carson High graduate, could remember meeting Cowee for the first time around 1996. She’d moved back to the capital city after college in Southern California where she studied poetry. She was at the Brewery Arts Center for something unrelated when she overheard Cowee and another person talking. She introduced herself.

“Just a really nice older gentleman,” she said. “He wanted everyone to be involved in poetry, so he was very welcoming. And then he mentored me significantly after that.”

The two poets became friends. Breeden had begun writing poetry in high school and joined Ash Canyon Poets upon returning to Carson. Even when she moved to Berkeley, Calif. — returning to Carson in the new millennium — she kept in touch with her poet friends. She said Cowee taught her how to submit to literary journals and track submissions.

“He walked me through all of that and was that way to anyone who wanted to learn or talk about poetry. He was always available,” she said.

Back in Carson, Breeden rejoined Ash Canyon Poets every Friday, sometimes at a local church, sometimes at BAC, and even at the nursing home where Cowee spent his final years.

“There was no competition in it at all,” she said of the camaraderie. “It changed my outlook because I was coming out of college, and I was a little competitive, and it really changed the way I thought about how to be in the world.”

Years later, Breeden visited Comma Coffee in downtown Carson for this story, a place where Cowee participated in the city’s long-running “Jazz and Poetry” events. In 2016, she was part of the Mile High Jazz Band’s tribute to Cowee which included a chapbook of his work edited by Rita Geil. The chapbook included poems not found in his book and his “nursing home” poems that earned him the NAC award the year he died. The latter poems can be dark, peopled by dementia patients, medical staff and a sense of despair. Some are also illuminated by a stubborn beauty.

“He was unable to write at that point, and so I transcribed the poems for him,” Breeden recalled. “So, he would say them out loud to me, and I would write them up and then read them back to him, and he’d give me any edits, and I’d rewrite them, and then I typed them up and turned them into the arts council for him. So, when he won the arts council, it was those nursing home poems we worked on together.”

Of her mentor, Breeden said his work is grounded in place and “also people.”

“But he had ideas in his poems, too,” she said. “I guess a little bit of everything.”

Cowee’s sense of place owes a lot to the Carson City area, from the mountains on the west side to desert on the east. His poems touch on history, such as the V&T engine shops in downtown Carson and their demolition in the 1990s, or the beginning of Candy Dance in Genoa in 1919. His poems explore geography, flora and fauna, alternate between love and sadness. They reach for a greater world of society and politics, settle on a line about music or accounting. They are intense artifacts of a man possessed by the spirit of poetry but cognizant of his own mortality.

“The Mountain Contemplates Its Scree” reads:

“When, he wonders, will he be transformed

into wild onion, mule ear, or skunk cabbage,

be bound to root on the stream bank,

live in mute witness to his creation

as words decompose into the dark humus.”

Breeden said if Cowee did stop writing toward the end of his life, “he was probably writing in his head.” He couldn’t physically write anymore, she said, but had fully formed poems he could voice for transcription, down to the line breaks, every word choice.

“He was composing in his head full pieces,” she said. “It was really impressive.”

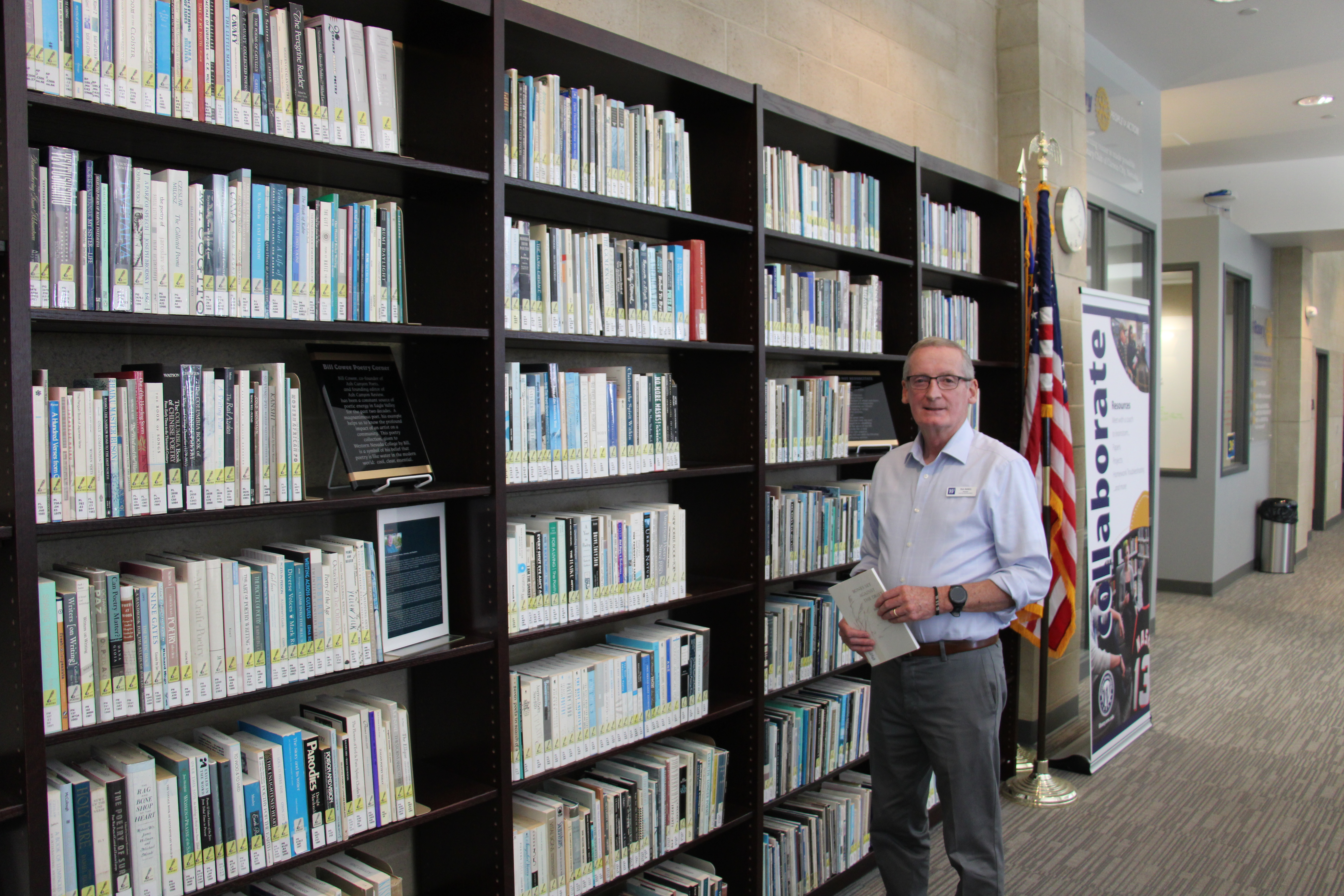

Ron Belbin, Western Nevada College director of learning and innovation, at the Bill Cowee Poetry Collection in the college’s library on Sept. 17, 2024.

Ron Belbin, Western Nevada College director of learning and innovation, at the Bill Cowee Poetry Collection in the college’s library on Sept. 17, 2024.Cowee the benefactor

What we know about Cowee is his poetry came with a generous spirit. He edited literary journals, co-directed a writers’ conference.

“Perhaps most unknown about Bill, he labored to support the poets in the prison poetry workshop I have taught at Northern Nevada Correctional Center for many years. In fact, one year they elected to put a painting of him on the cover of their journal, Razor Wire,” Griffin wrote.

In 2007, Cowee donated his poetry collection to the library at Western Nevada College in Carson City.

“There are about 1,200 volumes that are currently catalogued, and then there are boxes of papers that we have not had the opportunity to go through yet… we don’t have an effective archive at the moment, so we have quite a bit that has not been catalogued,” said Rob Belbin, WNC director of learning and innovation.

Belbin said Cowee’s collection is available to students and anyone with a library card. The books are all poetry including contemporaries from around the world.

“It’s a huge collection that represents a lifetime devoted to the subject,” Belbin said.

Of the six boxes of papers in WNC’s possession, Belbin believed they contain some pamphlets and printouts of other works. He didn’t know if Cowee put new work of his own in the boxes. Belbin said the library needs someone with the rights skills to handle the papers delicately and also the necessary supplies for preservation.

“About 20 years ago, I took a class of poetry at WNCC,” Cowee himself said of the donation in 2007. “Several of us decided we were having too much fun, so we formed the Ash Canyon Poets. From there I continued writing… and collecting.”

Belbin said WNC (formerly WNCC) created a separate policy for the Cowee collection. He said the books are not circulating very much, presently, but are available and accessible.

“It is a very important part of our larger collection, and we take responsibility very seriously, and it would be wonderful just to have resources to be able to highlight it more… and get through Bill’s many boxes that we have.”

Breeden thought she’d helped pack the boxes but didn’t know if they had new poems by Cowee. How to get people interested in the library’s collection, and in poetry in general, was a question posed to Breeden.

“Poetry encapsulates a moment in a way that fiction and nonfiction don’t really do,” she said. “I think it helps you kind of figure out how you’re living in the world and how you want to live in the world. For me, it’s a process. It’s not just writing. It’s a life process. I think for anyone who is thinking about reading poetry or writing poetry, that’s one way to look at it: it’s a way to process.”

Breeden said poetry, as embodied and affirmed by Cowee, pays special attention to the world, paring language to what’s an essential idea, thought or moment, to “what’s really important.”

“If you can do that in life, then even better,” she said, “if you can figure out what’s really important.”