Nate Delaney, parks maintenance coordinator with Carson City Parks, Recreation and Open Space, got this picture of a rainbow over Lone Mountain Cemetery’s Civil War monument circa 2022.

Nate Delaney/Special to the Appeal

Perhaps the most famous stagecoach driver in the world eternally rests in the southwest corner of Lone Mountain Cemetery in Carson City. Hank Monk was known for setting speed records over the mountains in the 19th century. He’s been described as reckless. Today, his original headstone lies on the ground, and a new marker watches over unmarked graves to the west of him as well as those horseless cars zipping by on Roop Street, drivers potentially unaware of the history so close to them, beneath them.

Monk, who died in 1883, was immortalized in Mark Twain’s “Roughing It” for giving New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley a ride to Placerville, Calif. Monk was celebrated in his time and is still celebrated today by those who maintain the cemetery.

“I’m a big offroad desert racer, and to me, Hank Monk was the first desert racer ever,” said Nate Delaney, Carson City Parks, Recreation and Open Space parks maintenance coordinator.

Less is known about the barren-looking field just west of Monk’s grave. In the spring and summer months, spears of cheatgrass poke out of the dirt. Beyond the site are cars, trees, buildings, C-Hill and the Carson Range. Park staff and local historians believe there are hundreds of unmarked graves in this southwest corner, where Monk’s gaze has settled. In this juxtaposition between the famous and the obscure, the drama of life plays out in death.

“That’s one thing that fascinated me about historic cemeteries was that the people were really segregated in society, culturally and everything in the city — they had different organizations, different fraternal societies and things like that, different churches — and then when they died, they were also segregated in death,” said Cindy Southerland, Carson City resident and cemetery historian.

Southerland once wrote, “Why are historic cemeteries important to society today?” Then answering her own question, she wrote: “The grounds are often the only record or artifact remaining to share the story of the community and the individuals who shaped it.”

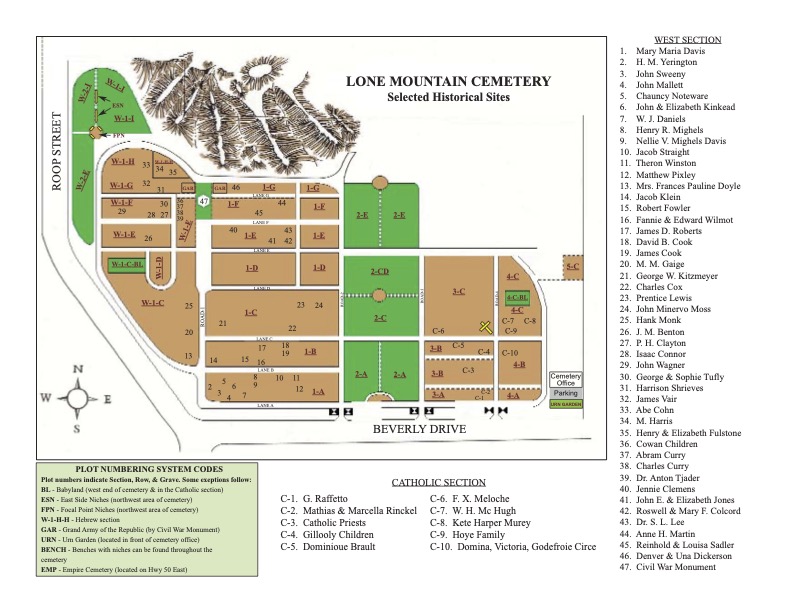

A map from Carson City showing the layout of Lone Mountain Cemetery in Carson City and notable gravesites. Courtesy photo

A map from Carson City showing the layout of Lone Mountain Cemetery in Carson City and notable gravesites. Courtesy photoMany shaped the frontier town of Carson City, which was established in 1858 before Nevada statehood in 1864. Carson’s founder, Abraham Curry, is among the famous pioneers and politicians resting in Lone Mountain Cemetery today. Henry Yerington is another. The list of famous people at Lone Mountain is long. So is the list of pioneer children buried there. And the list of veterans ranging from the Civil War era to modern-day conflicts. Before consolidation by the city in 1971, what’s known as Lone Mountain Cemetery was actually seven different cemeteries divided by religion or fraternal order. According to the city, approximately 11,000 people are buried across more than 32 developed acres. That total includes approximately 2,200 veterans.

Some headstones date back to the 1860s. Wooden markers effaced by weather look like props from a Western film. Some markers made of sandstone, quarried at the historic Nevada State Prison, show severe cracks or lie broken. Other monuments made of white bronze (a zinc alloy) are hollow — useful during prohibition years for hiding moonshine.

To the north of present-day plots sprawl a dozen acres of sagebrush, where the city plans to gradually expand the cemetery for new burials.

“We do around 140 to 150 burials a year,” said Nick Wentworth, the city’s parks project manager. “Every year there are more and more cremations and less and less full casket burials.”

Staff members like Wentworth, Delaney and cemetery administrator Lee-Ann Keever anticipated changes in how the deceased would be interred and remembered, foreseeing more cremations and niche walls. At the same time, they looked upon their duty of tending the old grounds as sacred work.

“The care that Nate and the crew and all of us expend — that’s our way of remembering those individuals,” said Keever. “This is sacred ground, and taking care of them is a sacred calling.”

“Everybody who comes here kind of has a different feeling or take on ghosts or spirits or bad or good or whatever,” said Delaney. “The way I see it is all the people here we are looking after, and they’re very happy to have us cleaning their grave, pulling the weeds, mowing the lawn, trimming their headstones, straightening, fixing it, whatever we can do to make their plot better… I always think the people are above looking down and smiling, happy that we’re here.”

Weeding, mowing, mapping plots and other tasks are not impersonal as staff members have personal connections to cemetery residents. Keever’s grandfather, father, sister, aunt and uncle are buried at Lone Mountain.

“When I go past my dad’s grave, I wave. Or my sister’s. It’s a way of keeping in touch with them,” she said.

Wentworth buried his mother, a veteran of the U.S. Air Force, in one of the older sections. Plots for veterans are still free.

“I always felt a bigger responsibility to all the plots that don’t have anyone here anymore, or maybe those descendants have forgotten,” said Wentworth. “We have to remember. It’s our duty to take care of all of those plots. They all deserve the same honor. That’s regardless of if it’s Henry Yerington or one of the governors or whoever, or if it’s somebody who is out there who doesn’t even have a marker on their plot. It’s all the same. Once they’re here, it’s more of a level playing field.”

Southerland exhibited similar affection for the gravesites. A historian, she said she avoided the “ghoulish aspects” of cemeteries. Instead, she preferred focusing on the complexity of interwoven histories. Lone Mountain Cemetery is like a palimpsest where new entries continually rise on old histories. However, where Wentworth saw a level playing field, Southerland saw more social stratification, perhaps because she was a researcher summoned in the fall of 2000 when human remains were found during construction on adjacent Roop Street.

“They dug us a trench that was not reinforced, but we only had one day, so we just worked really hard and tried to be safe, and we were only able to retrieve six bodies,” recalled Southerland, who worked with staff at the Nevada State Museum on the site. “There were more in there. The ones that we did find and retrieve were about six and a half feet below ground level, and they were about three feet apart, but you could see that some were below them. You could see evidence the earth had been disturbed, so we assumed there were more bodies below.”

Carson City resident and cemetery historian Cindy Southerland on June 10, 2024, in the southwest corner of Lone Mountain Cemetery, where she believes there are possibly hundreds of unmarked graves. Scott Neuffer/Nevada Appeal

Carson City resident and cemetery historian Cindy Southerland on June 10, 2024, in the southwest corner of Lone Mountain Cemetery, where she believes there are possibly hundreds of unmarked graves. Scott Neuffer/Nevada Appeal Sent to UNLV for research and later returned to the museum, the six skeletons were likely Chinese workers as indicated by artifacts found with them. Southerland said historically, Chinese residents would plan to have their bones exhumed, cleaned and returned to their homeland.

“But the ones who couldn’t afford it are the ones who ended up still here in Carson or anywhere, really,” she said. “They could have been doing mining. They could have had gardens. We know some had businesses in town. They had restaurants. It was quite a community.”

Carson had a thriving Chinatown, Southerland pointed out, which dwindled in the mid 20th century before the buildings were razed to make room for state buildings.

“They all made a contribution to the city and the state,” she said. “They contributed to the society and culture of Carson for decades.”

Southerland believed more Chinese residents and indigent people from the formative years of the city were buried in the southwest corner of the cemetery, under Roop Street and under what is now a commercial complex. A memorial at the relatively new commercial building to honor the deceased never materialized, she said.

“I would like to see a memorial of some sort be erected,” she said. “Maybe something on a donation basis. I think it would be an appropriate thing to memorialize them.”

Watching traffic on Roop Street, Southerland noted it’s important to preserve and promote history.

“We lose a lot of our history every day,” she said. “Once it’s gone and there is not a written record or notice of it, it’s gone. You lose it.”

Despite losses, Lone Mountain Cemetery is a place where history thrives and touches the present. Every Memorial Day weekend, volunteers congregate on the cemetery’s central lawn. They distribute miniature American flags and proceed to place them beside veteran gravesites, thousands of them until the entire area is decorated. At the end of the weekend, the volunteers return to clean up. The flags disappear, and the cemetery’s eternal residents wait for another year.