Col. James M. Gavin, U.S. Army, commanding officer, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, with his men before Operation Husky, on July 9, 1943. Alfred Pawley, whose son lives in Carson City, served in that unit. (U.S. Army photo)

Alfred Pawley served in the U.S. Army during World War II and was a paratrooper on D-Day.

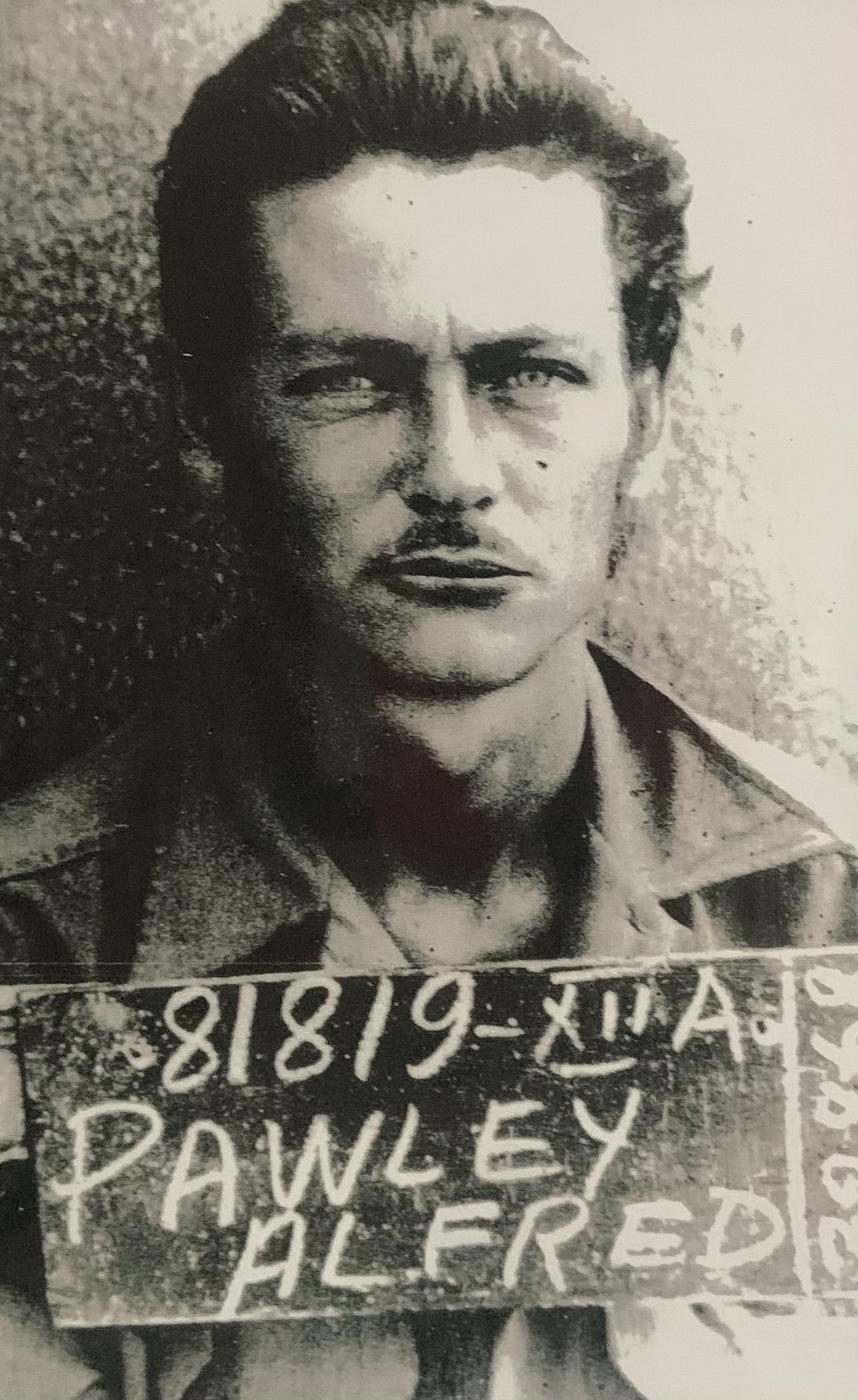

Alfred Pawley served in the U.S. Army during World War II and was a paratrooper on D-Day.  Alfred Pawley’s POW photo.

Alfred Pawley’s POW photo.